Casapuerta. Fuentesal Arenillas

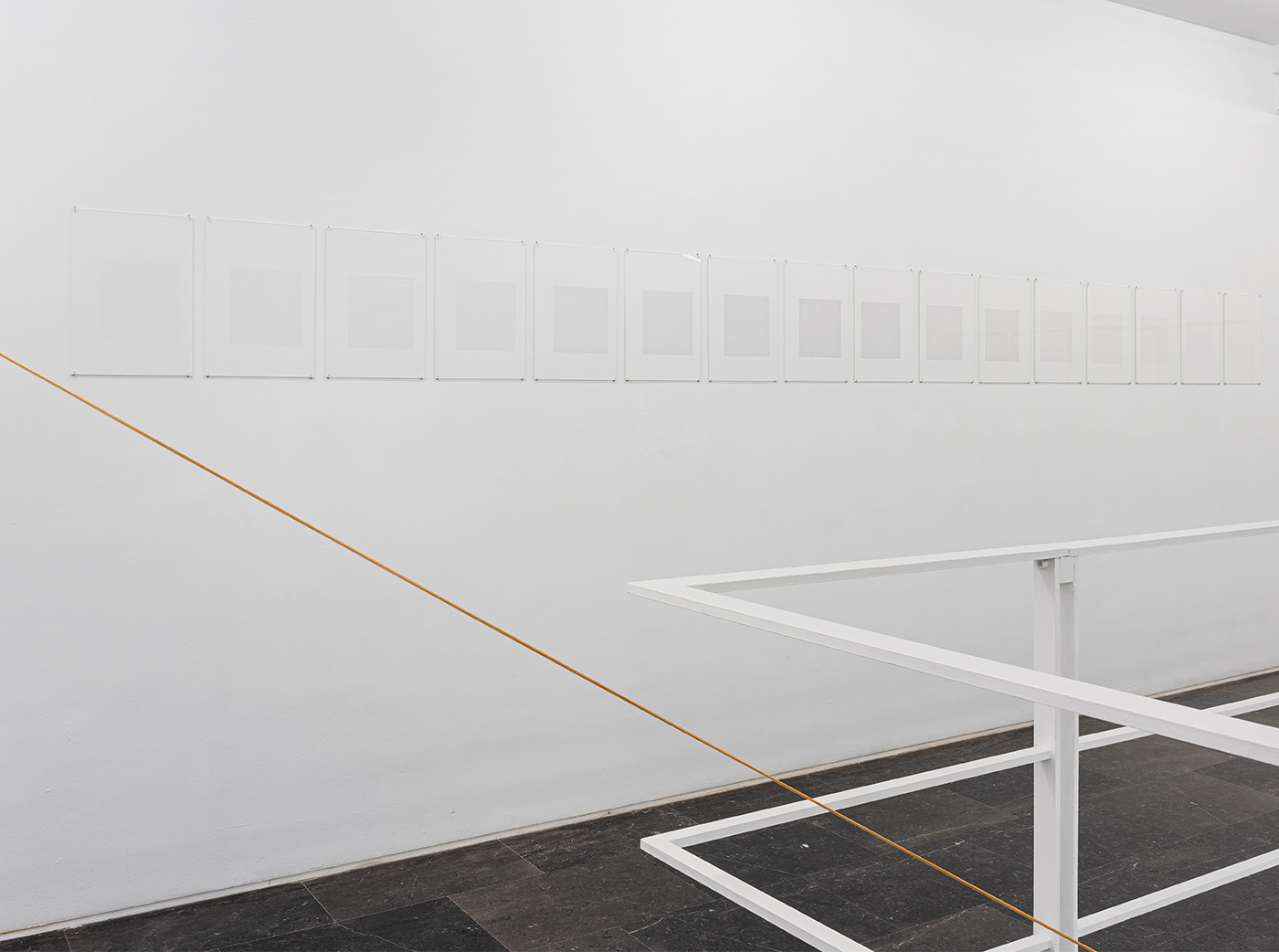

Casapuerta, 2022. Room 1. General view

Casapuerta, 2022. Room 1. General view

Aparejo II, 2022. Canvas, MDF, paint, pattern cardboard, pencil, wooden clothespins. 160 x 555 x 80 cm

Casapuerta, 2022. Room 1. General view

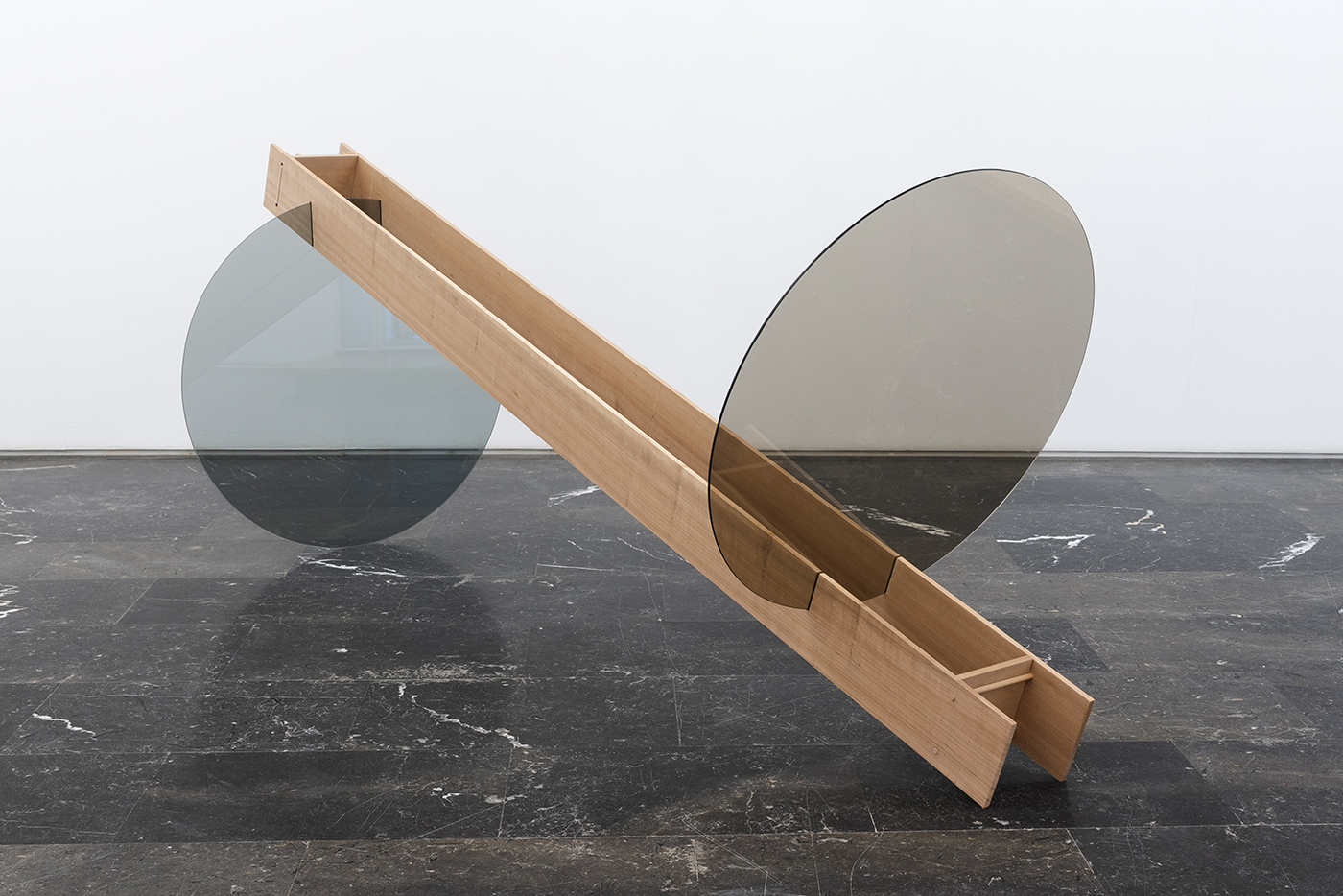

La mesa es el suelo de las manos, 2022. Tabletop glass, cherry wood. 105 x 90 x 250 cm

Aparejo I, 2022. (Detail) Canvas, MDF, paint, pattern cardboard, pencil, wooden clothespins. 130 x 80 x 70 cm

Casapuerta, 2022. Room 1. General view

Barraca, 2022. Pine wood, iroko, canvas, cardboard, rope. 90 x 53 x 20 cm

Casapuerta, 2022. Room 2. General view

Corre, vé y dile, 2022. Canvas, wood, paint, pattern cardboard, brass, printed image. 140 x 80 x 80 cm

Corre, vé y dile, 2022. (Detail) Canvas, wood, paint, pattern cardboard, brass, printed image. 140 x 80 x 80 cm

Julia y Pablo, 2022. Hand carved sapele wood. 25 x 40 x 22 cm

Casapuerta, 2022. Room 2. General view

Oye lo que traigo, 2022. Canvas, wood, paint, pattern cardboard, brass, printed image. 140 x 150 x 100 cm

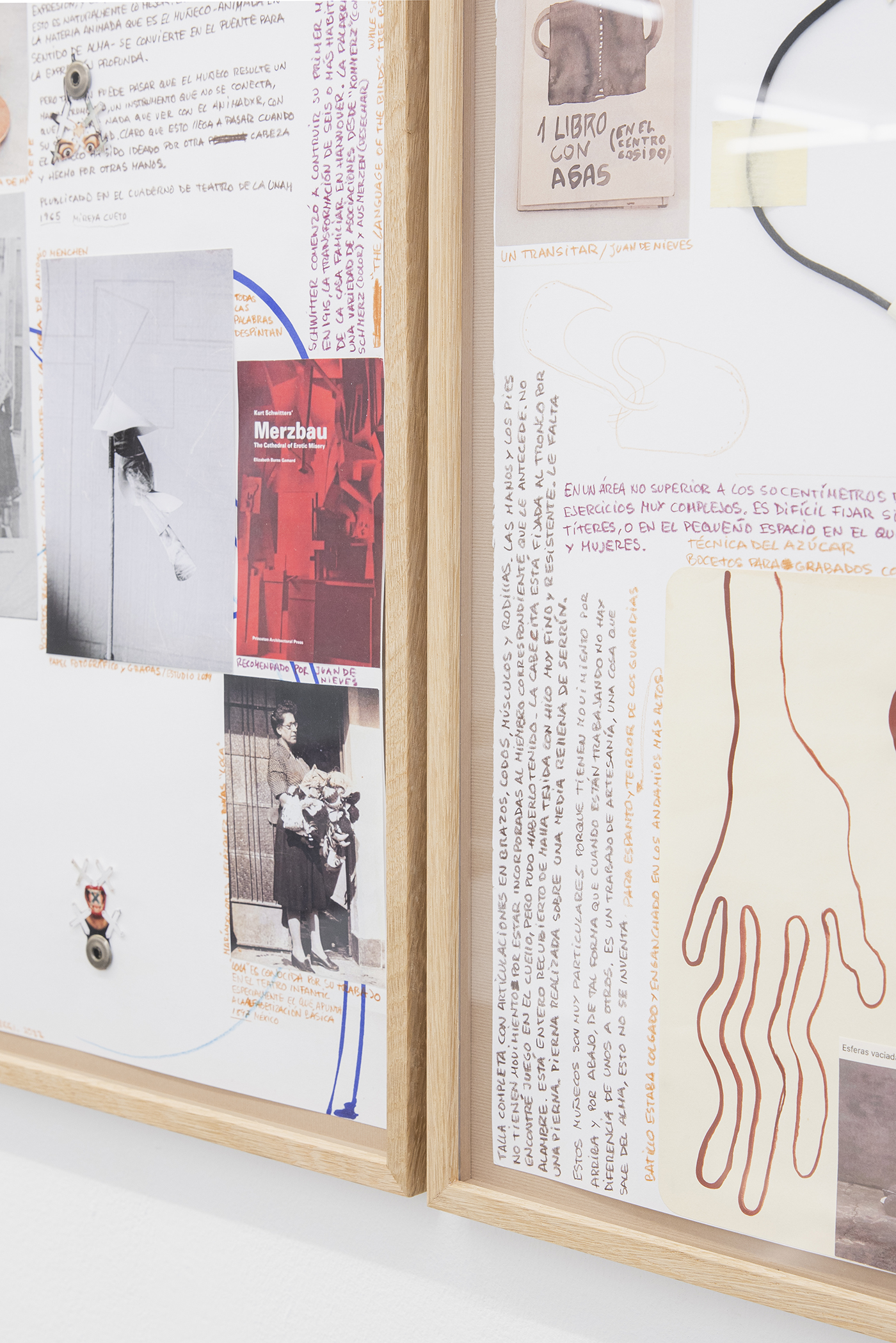

Un collar de ventanas, 2022. (Detalle) Mixed media on paper. 46 x 700 cm

Un collar de ventanas, 2022. (Detail) Mixed media on paper. 46 x 700 cm

Casapuerta, 2022. Room 3. General view

Guardacantón II, 2022. Iroko wood, MDF, canvas and pattern cardboard. 215 x 26 x 44 cm

Casapuerta, 2022. Room 3. General view

Casapuerta, 2022. Room 3. General view

Ellas I, 2022. Canvas, DM, pattern cardboard and chipboard. 120 x 38 x 70 cm

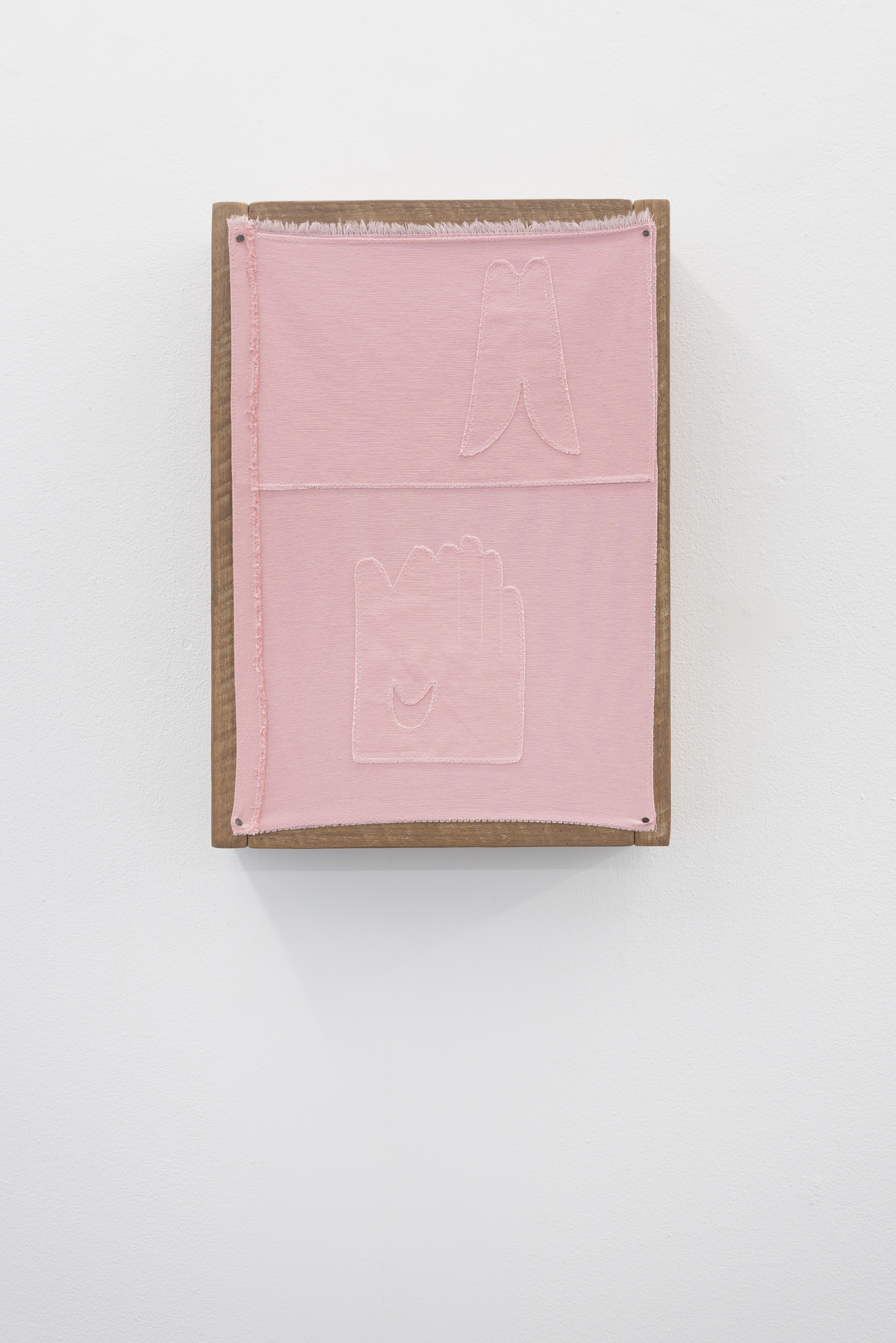

Viña III, 2022. Iroko wood, canvas and nails. 48,5 x 34 x 10 cm

Casapuerta, 2022. Room 3. General viewl

Guardacantón I, 2022. Iroko wood, MDF, canvas and pattern cardboard. 210 x 28 x 45 cm

Casapuerta, 2022. Wood, paint, canvas and cardboard. 123 x 63 x 32 cm

Casapuerta, 2022. Room 4. General view

S.T. (Familia), 2022. (Detail) Iroko wood, sapele, fland pine, mahogany, iron and vinegar. Chipboard, canvas and cardboard. 120 x 280 x 47 cm

Comisura II, 2022. Russian pine, sapele, canvas, cardboard, staple, rope. 210 x 80 x 15 cm

Casapuerta, 2022. Room 4. General view

Comisura III, 2022. Iroko wood, rope, canvas and pattern cardboard. 195 x 80 x 16 cm

S.T. (Familia), 2022. (Detail) Iroko wood, sapele, fland pine, mahogany, iron and vinegar. Chipboard, canvas and cardboard. 120 x 280 x 47 cm

S.T. (Familia), 2022. (Detail) Iroko wood, sapele, fland pine, mahogany, iron and vinegar. Chipboard, canvas and cardboard. 120 x 280 x 47 cm

La mesa es el suelo de las manos, 2021. Pine wood, glass table and linen. 80 x 90 x 140 cm

Press release

hosts

Selina Blasco

A title is in itself a kind of invitation to enter. Casapuerta is a liminal place, a hallway between the street and house, neither one nor the other, a place you pass through that extends towards the inside like a passageway beyond the thin line of the threshold. It is also a way out. They said: elastic casapuerta. The truth is that in both cases it is generally neglected and is treated like a corner or cranny. Choosing it means focusing on its peculiarities. This part of the building is, above all, passed through. Without having to ring because, as they said: the casapuerta is open. But you can also spend time there. To this end, although it is usually left bare, it sometimes has accessories and even subjects that are proper to it. They are compatible with passing through and, in fact, it is often better known for the things that might be found there. For instance, old dictionaries speak of an image or a lantern, and of pages waiting to accompany their master when he goes out. In times of Cervantes, the casapuerta was used to stable a mule. It has its own atmosphere and its own temperature. They said: the coolness of the casapuerta.

Given its complexity, a compound word was required to capture it. Generally speaking, there is a liking for compounding; they also said: guardstone. What matters is the connection. To explain that a symbol is one made up of two, Giedion tells us that Plato said that at certain festive gatherings the host gave his guests the gift of half a broken coin or ring when they were leaving, in such a way that, if the possessors or their descendants could match the two halves sometime in the future they would recognize each other. It’s a question of joining up the parts. Casapuerta –literally housedoor, an Andalusian archaism still in use— is not declined through its ending. As Perrate sings: “Corre, ve y dile usted a mi madre/ como me veo en esta casitapuerta/ revolcaíto en sangre.”1 In casitapuerta only the first part of the word is diminutized, because each element in the compound maintains its independence. Some uses open the imagination to others, which take shape through different forms of entwining them.

In the compound world there are emotional bonds. They said: our own relationship. And they said: how to live together. Here there is a way of recognizing oneself as a connection, like an agreement of different orders —joints— which, on the other hand, cannot exist without a body, without its size, without its weight, without its skeleton, without its wounds and without its flesh. Undertaking experiments based on compounds enables them to return once and again to what has already been done; it is a way of renewing the aforedone and preparing it to be something else. There is no unity and nothing is ever concluded. And that is also—and here I join in—the way this text comes into being, a writing that always goes back to the aforewritten. In this form of possibilities of coming into being, in this form of potentiality, there are no leftovers and no waste. The residual –this time said by Ángel González García— is what is missing. They said: sweeping is moving and gathering.

To make it visible, the joints are left bare; they are there in plain sight. They said: to be seen. And, indeed, it could well be an invitation to dwell on the parts and to examine their properties. In Galicia, on the other hand, this expression is used to describe a time of waiting, of resigned fate for what will happen for better or worse. A place of transit is time.

And they said: the hidden but not concealed. There is a way of working that brings the back (yes, they also said: underside) to the front, revealing the burrs, the biased cuts and the seams opened with the iron. In fact, what happens is that the distinction by opposition between contraries is rendered null. The process is associated with certain textile practices, like the perfect stitching that can be appreciated on the underside, coinciding exactly with the front. A form of making by displacement of the other. They said: slippage. One of the variants would be patterns, the materialization of different forms that can adopt a thing or a subject while it remains itself. Others seem to the result of a work of extension and unfolding of certain volumes a posteriori, instead of a priori, to the tailoring.

Compounding speaks of the foldability that enables assembly and disassembly. It calls for provisional fixing that can be easily fitted and unfitted. Here it is possible to make and unmake, and over the course of the back and forth it may happen that some parts demand their freedom, they separate and build themselves into something else. It is the making of the unfinished, the never-ending and, if looked at wisely and with a sense of humour, allowing the world to be seen in many ways. The liking for finish is confined to surfaces; for instance, the soft touch of certain woods when directly polished or after being bathed with a thin coat of paint. They said: the memory of the hands.

The assemblage adapts to the personality of artefacts that inhabit certain provisional spaces like stage settings or transit areas, and also to the transportable chattel of temporary rooms. Here “the movable” is dismembered and unfolded in an unordinary order that is reinvented while continuing to recognize itself as what it is when it is arranged and used as it should. They said: the table is the floor of the hands. Everything can be disassembled and reassembled (sometimes stored in boxes) but in other ways that, precisely in a kind of journey in the opposite direction, say what they are in different forms and shift them away from the conventional. The most intimate form: the pages of a notebook, a notebook of memory which contains loads of cultural references that will never be literally materialized, are pulled out and divided among friends (they said) so that they could join in this binge of compounding. They said: pleasure. To make a return to collective making, one has to string together again, to join together in succession. They said: we keep each other company.

And they said: out of place, but the to-and-froing does not mean a lack of attention to spaces, rather quite the contrary. Things are not what they are because they accrue the memory of the places where they were made and where they have lived. They are impregnated with their character. Bachelard tells us that this happens no matter how much we try to erase singularities. Talking about the phenomenology of the cellar and the garret, he wrote that “in our civilization, which has the same light everywhere, and puts electricity in its cellars, we no longer go to the cellar carrying a candle. But the unconscious cannot be civilized. It takes a candle when it goes to the cellar.” He was not acquainted with the neighbourhood of Santa María in Cádiz, where there are cellars on street level in buildings that were built to maximize habitability on the basis of excavating, making the most of the level. They have natural light and some are — like garrets — cluttered with things, riddled with information. As Bachelard also wrote about the function of inhabiting as an imaginary replica of the function of building, it is inevitable to think that, in order to produce here, you not only have to be able to open a physical and mental space (they said: to leave), but also to outline well, to work with clarity.

“The unmovable”, in these times, may not even reach Brodsky’s room and a half. The foolhardy would love to have the sky as a ceiling, the breeze for a hat (we’ve also heard Perrate sing about this). The fearful would look for the shelter of a roof or a similar refuge where they would be under cover. They said: look after or protect. And they said: from the sunshade or the hat. Here there is another form of conjuring the body by displacement that, this time respecting the ‘natural’ order, expresses it in the form of another by allusion. They said: filling the gap. A stand-in for the head would be a wide-brimmed picture hat dolled up with the whole shebang by a primpy person who adorns it with little treasures attached, as always, to the underside because it is closer to the face and is the pink colour of heart pink, with cards or images that are looked at and treasured from desire (they said).

Displacement. They said, finally: moving house. 2 Buon lavoro; a rivederci.

—

1 Run, go and tell my mother / how you saw me in that casitapuerta / wallowing in blood.

2 All the words in italics are taken from a list Julia and Pablo sent to me while together in August, in many moments of talking while looking at the sun, of rubbing up together, of pleasure.