Boiler Room. SLURP, GLUG. Esther Gatón

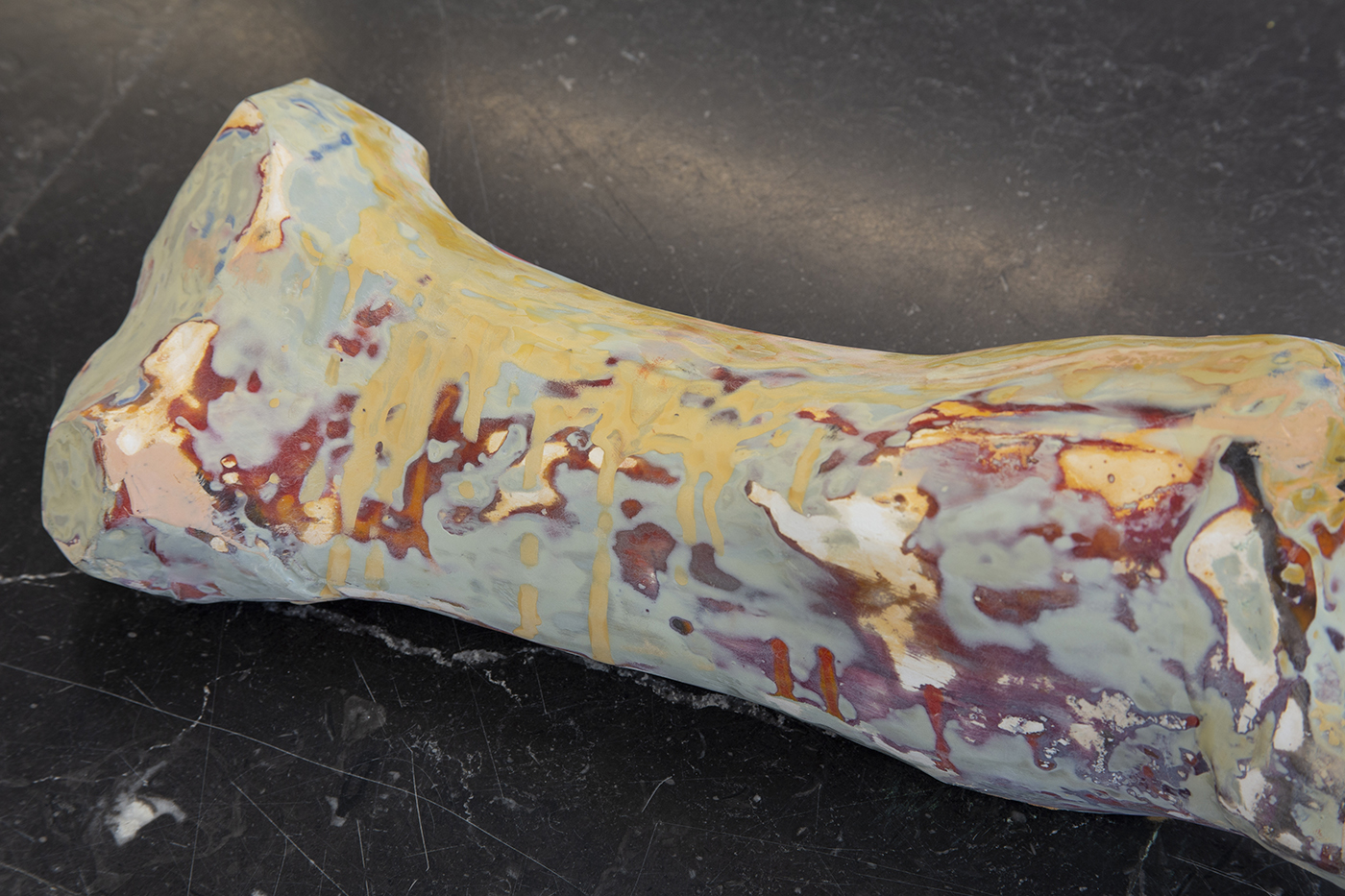

Chilla, se retuerce. Se hace más y más grande, 2019. Rusty iron, handicraft putty, car body filler, artificial oxidant, epoxy resin, transparent blue pigment and paint of the following colors: Aztec gold, Tennesee blue, gold rosé, champagne, pearl, graphite, violeta and red. 47 x 87 x 75 cm

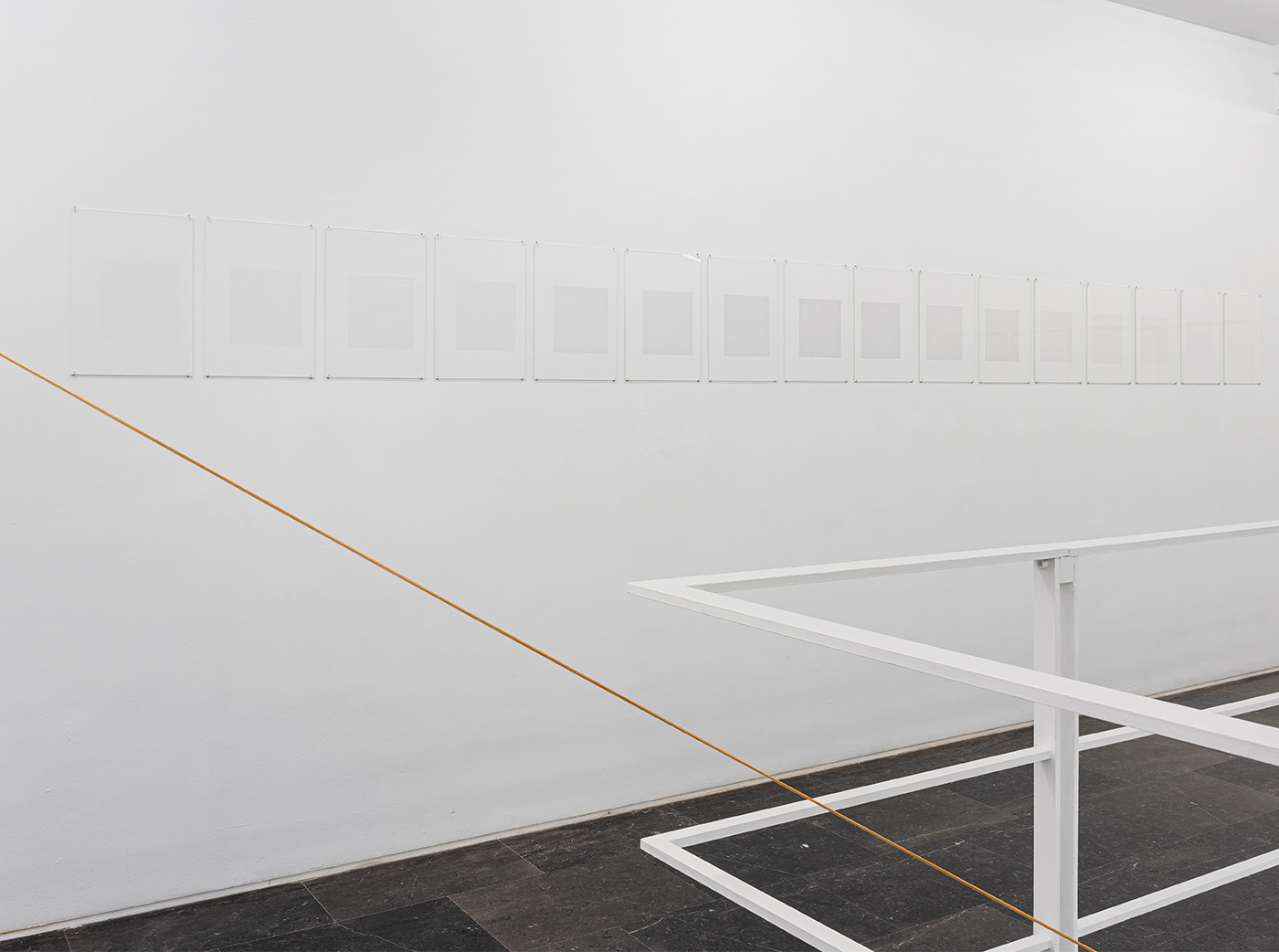

SLURP, GLUG, 2019. Chicken wire, plaster, hessian, resin, pigments, rusty iron, handicraft putty, car body filler, artificial oxidant, epoxy resin, transparent blue pigment and paint of the following colors: Aztec gold, Tennesee blue, gold rosé, champagne, pearl, graphite, violeta and red, Variable dimensions

SLURP, GLUG, 2019. Chicken wire, plaster, hessian, resin, pigments, rusty iron, handicraft putty, car body filler, artificial oxidant, epoxy resin, transparent blue pigment and paint of the following colors: Aztec gold, Tennesee blue, gold rosé, champagne, pearl, graphite, violeta and red, Variable dimensions

SLURP, GLUG, 2019. Chicken wire, plaster, hessian, resin, pigments, rusty iron, handicraft putty, car body filler, artificial oxidant, epoxy resin, transparent blue pigment and paint of the following colors: Aztec gold, Tennesee blue, gold rosé, champagne, pearl, graphite, violeta and red, Variable dimensions

Un volcán explota y vuelve a convertirse en montaña, 2019. Chicken wire, plaster, hessian, resin and pigments. 16 x 45 x 17 cm

Chilla, se retuerce. Se hace más y más grande, 2019. Rusty iron, handicraft putty, car body filler, artificial oxidant, epoxy resin, transparent blue pigment and paint of the following colors: Aztec gold, Tennesee blue, gold rosé, champagne, pearl, graphite, violeta and red. 87 x 113 x 92 cm

Chilla, se retuerce. Se hace más y más grande, 2019. Rusty iron, handicraft putty, car body filler, artificial oxidant, epoxy resin, transparent blue pigment and paint of the following colors: Aztec gold, Tennesee blue, gold rosé, champagne, pearl, graphite, violeta and red. 45 x 170 x 135 cm

SLURP, GLUG, 2019. Chicken wire, plaster, hessian, resin, pigments, rusty iron, handicraft putty, car body filler, artificial oxidant, epoxy resin, transparent blue pigment and paint of the following colors: Aztec gold, Tennesee blue, gold rosé, champagne, pearl, graphite, violeta and red, Variable dimensions

Texto

“something is growing by itself”. But the frontier between care and domination

is not only a slippery slope, but anything that grows by itself never does so alone, but rather in the company of other elements, other lives, other things. Gardens, like cities, are ambiguous places: we are in them, but also outside them. A plant in a plant pot is the convergence of nature and culture. The roots adapt to the space and shape of the plant pot. A lot of plants are indoors, but belong outdoors. Do they feel the difference? As in art, gardens are an aesthetic artefact linked to thought, but also to ways of knowledge that appear with material practice. Techne has its own episteme. The wish to preserve things entails denying the passing of time, and the life that this gives rise to, transforms and discards. What if it were possible to have an exhibition that allowed light from outside, rain, night, wind, dust, bangs and breakage, movement of things, iridescence or disorientation of meaning? And what if all these elements were contained in it, attached to the surface of things? Could it not therefore be an exhibition of a biological system that could grow “by itself”? An exhibition as a third landscape, a residual, transitory space, outside planning, power and submission. An exhibition of items vulnerable to themselves, removed from the deliberate action of human beings. An exhibition as a process of actions that are external to it. An externality that is evident in the internality.