Kobold. Javi Cruz

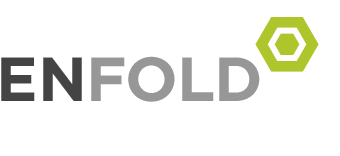

Javi Cruz. Kobold (La cueva), 2014 - 2022. Ink drawing and offset printing. 60 x 113 cm. / Kobold (el cielo), 2023. Plaster, cobalt blue, tile, esparto grass, pine wood, steel. 120 cm x 240 cm ø.

Javi Cruz. Kobold (La cueva), 2014 - 2022. Ink drawing and offset printing. 60 x 113 cm.

Javi Cruz. Kobold (La cueva), 2014 - 2022. Ink drawing and offset printing. 60 x 113 cm.

Javi Cruz. Kobold (Fátima), 2023. Wall carving, Virgin figure with rain predicting mantle. Variable measures.

Javi Cruz. Kobold (Fátima), 2023. Wall carving, Virgin figure with rain predicting mantle. Variable measures.

Javi Cruz. Kobold (el cielo), 2023. Plaster, cobalt blue, tile, esparto grass, pine wood, steel. 120 cm x 240 cm ø. / Kobold (La historia), 2023. Offset printing on found paper. 21 x 3,2 cm.

Javi Cruz. Kobold (el cielo), 2023. Plaster, cobalt blue, tile, esparto grass, pine wood, steel. 120 cm x 240 cm ø.

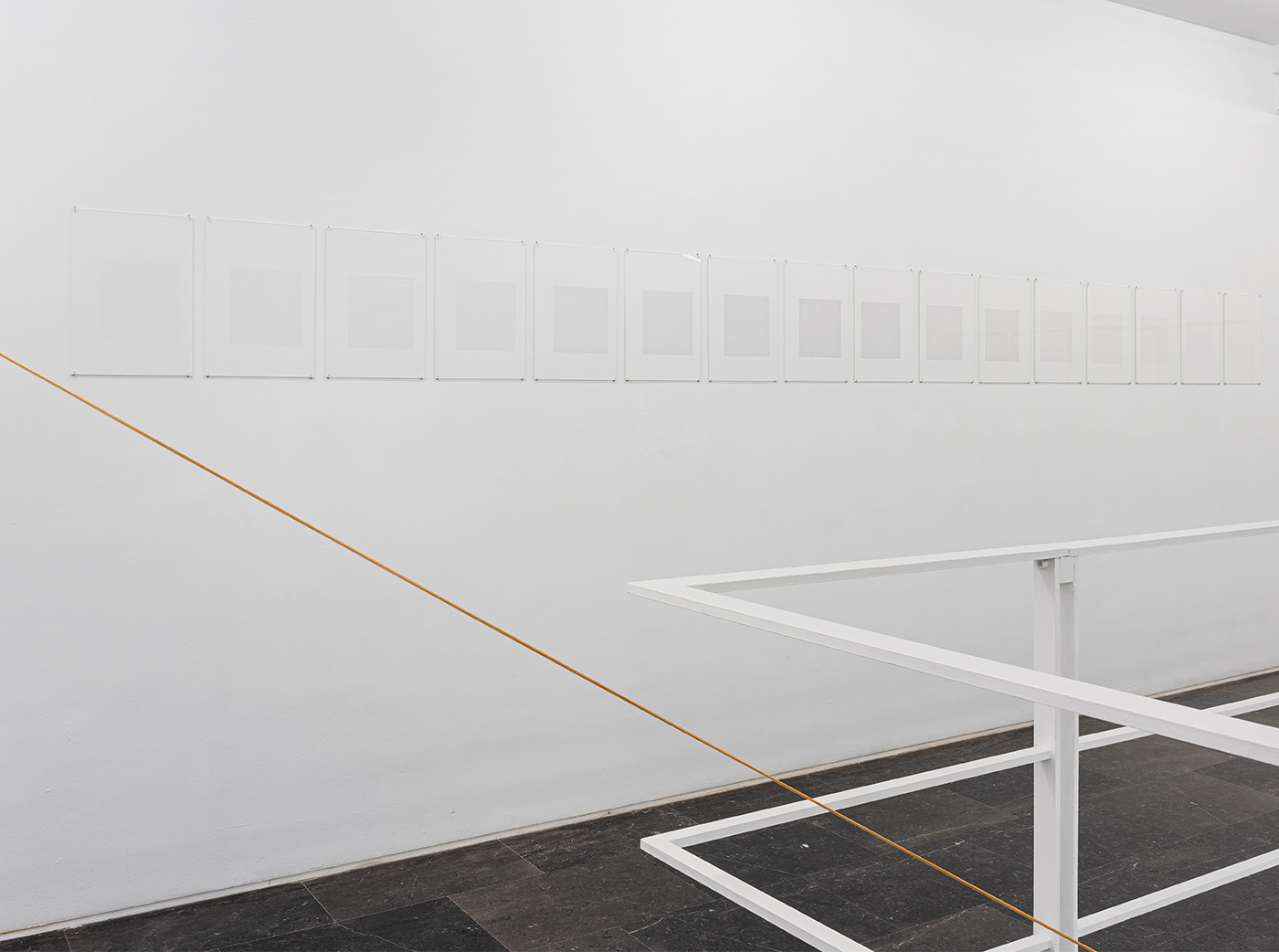

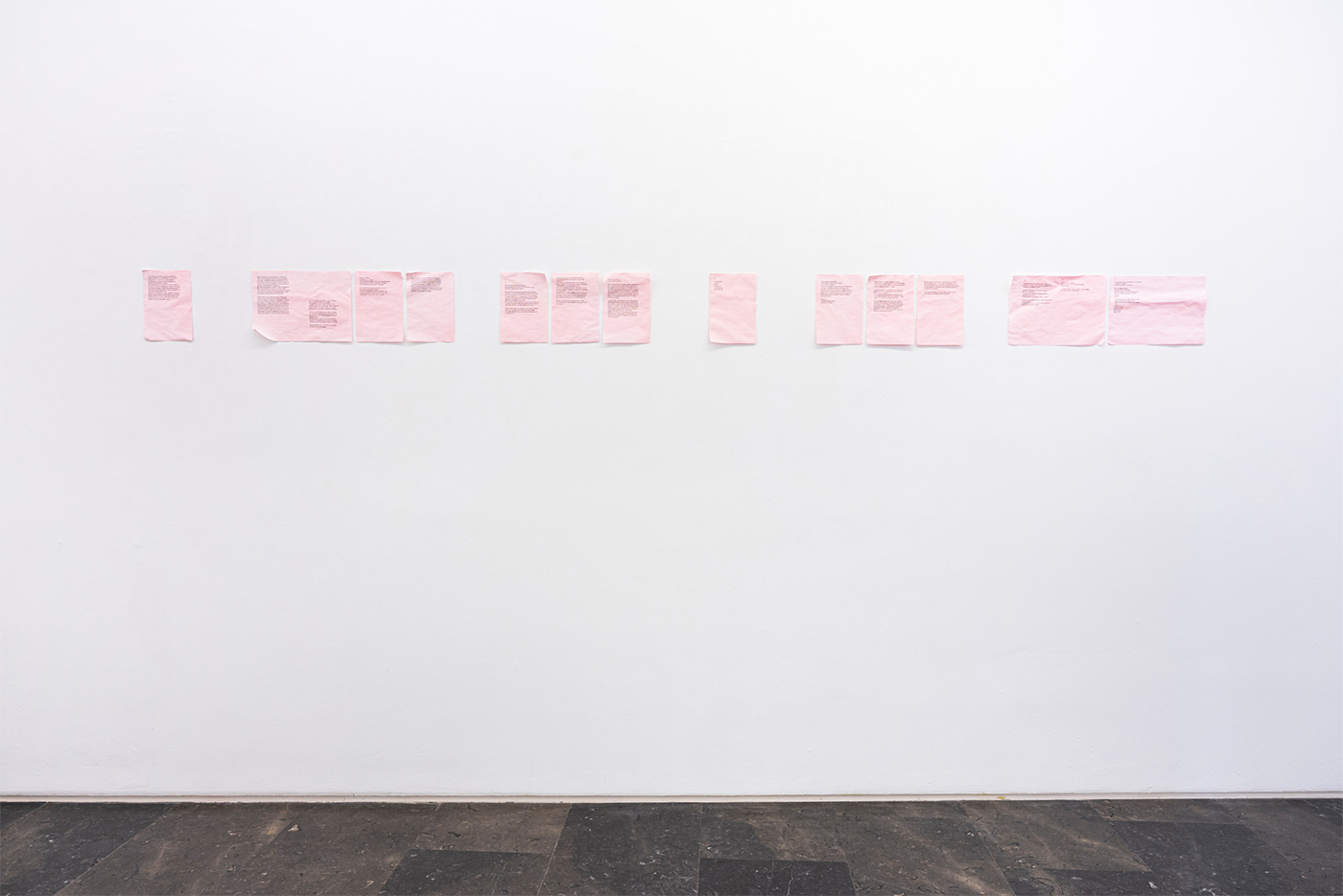

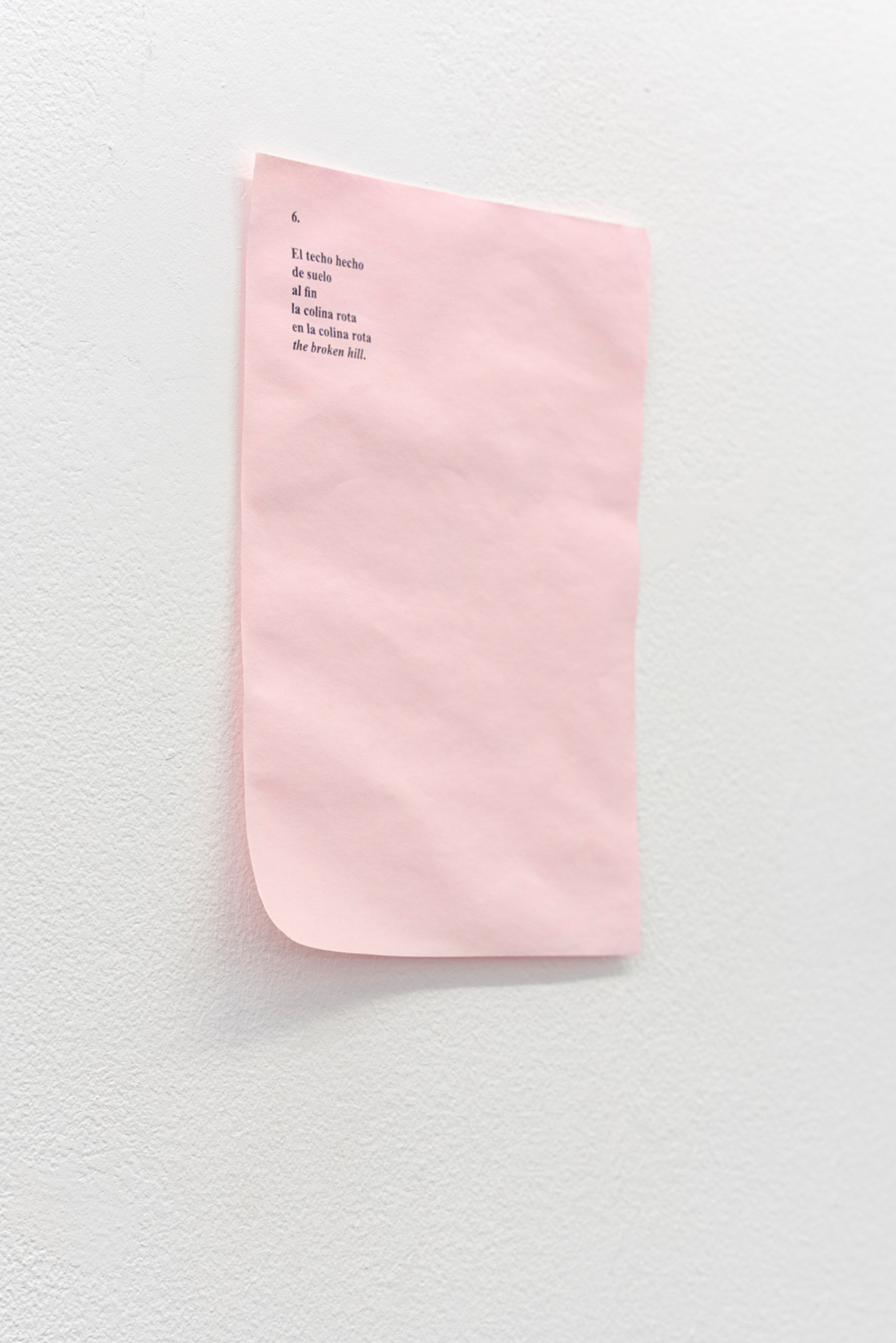

Javi Cruz. Kobold (La historia), 2023. Offset printing on found paper. 21 x 320 cm.

Javi Cruz. Kobold (La historia), 2023. Offset printing on found paper. 21 x 320 cm.

Javi Cruz. Kobold (La historia), 2023. Offset printing on found paper. 21 x 320 cm.

Javi Cruz. Kobold (Los ojos), 2023. Flint and iron. 8 x 12 x 2.5 cm.

Javi Cruz. Kobold, 2023. Room 3. General view.

Javi Cruz. Kobold (Las lluvias II), 2022. Linseed oil, gentian violet and raindrops on Arches cotton paper 345 gr. 250 x 130 cm.

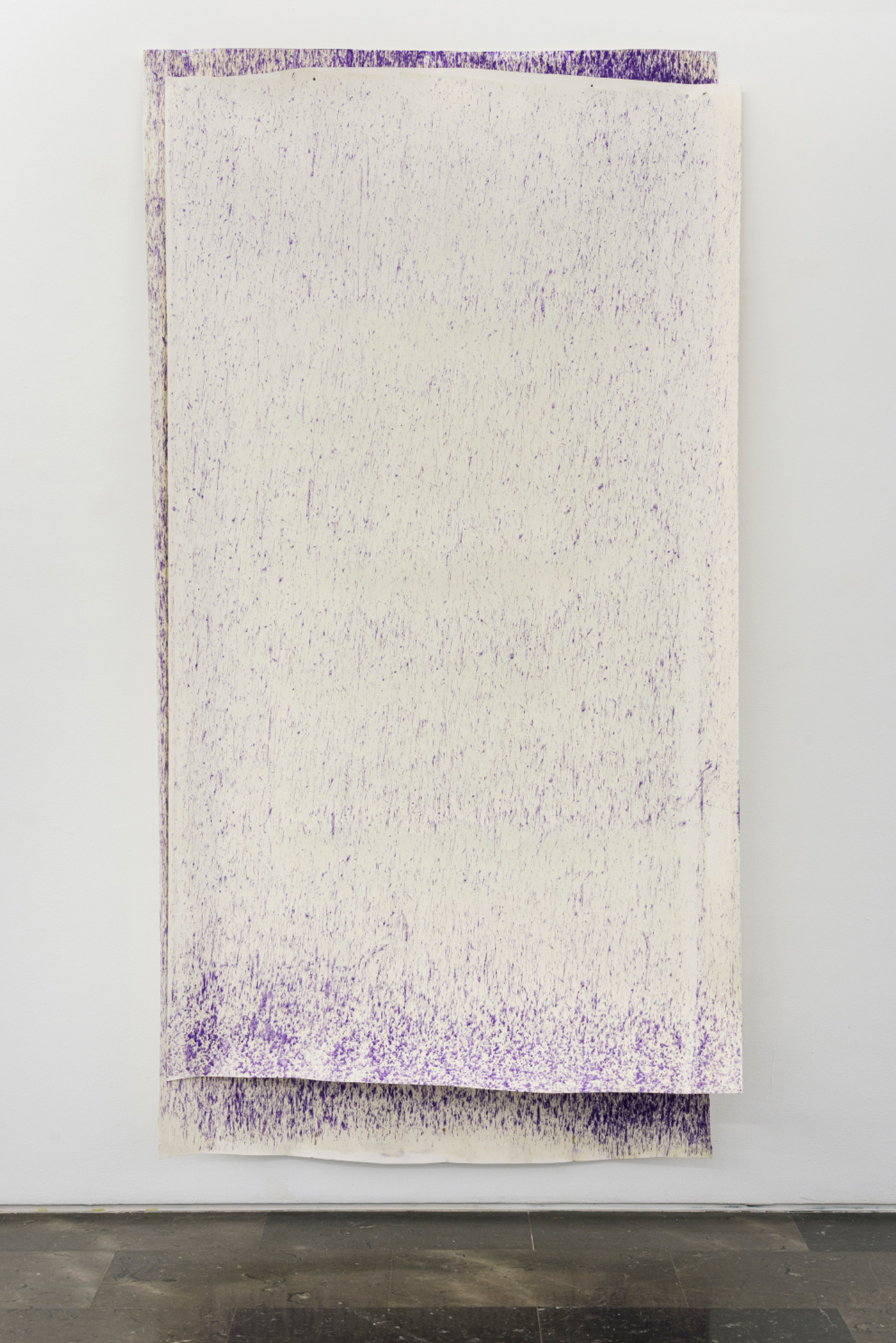

Javi Cruz. Kobold (Las lluvias III), 2022. Linseed oil, gentian violet and raindrops on Arches cotton paper 345 gr. 250 x 260 cm.

Javi Cruz. Javi Cruz. Kobold (Las lluvias V), 2022. Linseed oil, gentian violet and raindrops on Arches cotton paper 345 gr. 250 x 135 cm. / Kobold (Las lluvias III), 2022. Linseed oil, gentian violet and raindrops on Arches cotton paper 345 gr. 250 x 260 cm.

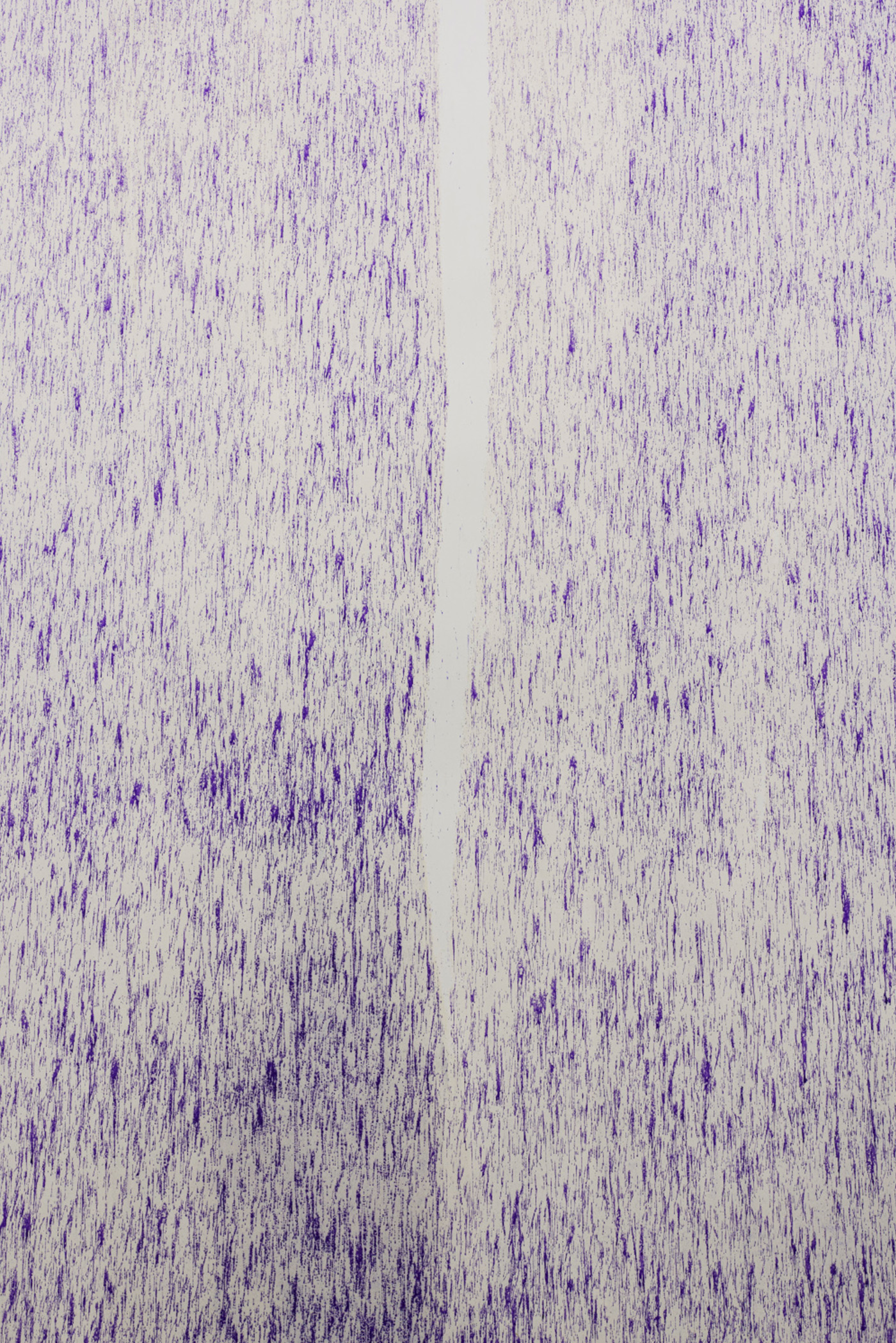

Javi Cruz. Kobold (Las lluvias III), 2022. Linseed oil, gentian violet and raindrops on Arches cotton paper 345 gr. 250 x 260 cm.

Javi Cruz. Kobold (Las lluvias III), 2022. Linseed oil, gentian violet and raindrops on Arches cotton paper 345 gr. 250 x 260 cm.

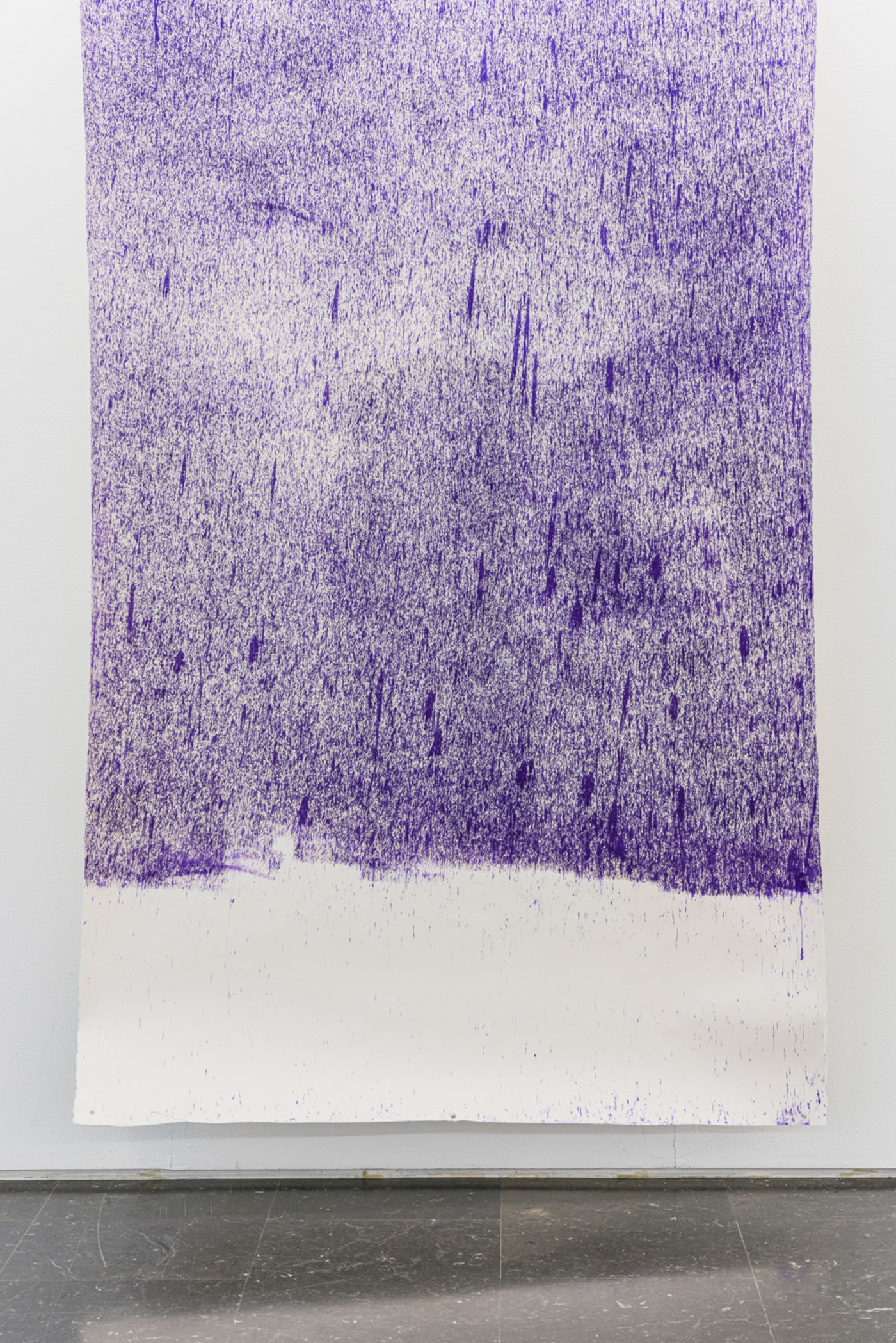

Javi Cruz. Kobold (Las lluvias V), 2022. Linseed oil, gentian violet and raindrops on Arches cotton paper 345 gr. 250 x 135 cm.

Javi Cruz. Kobold (Las lluvias V), 2022. Linseed oil, gentian violet and raindrops on Arches cotton paper 345 gr. 250 x 135 cm.

Javi Cruz. Kobold (Las lluvias I), 2022 - 2023. Linseed oil, gentian violet and raindrops on linen. 40 x 30 cm. / Kobold (Las lluvias IV), 2022. Linseed oil, gentian violet and raindrops on Arches cotton paper 345 gr. 250 x 135 cm.

Javi Cruz. Kobold (Las lluvias IV), 2022. Linseed oil, gentian violet and raindrops on Arches cotton paper 345 gr. 250 x 135 cm.

Javi Cruz. Kobold (Las lluvias I), 2022 - 2023. Linseed oil, gentian violet and raindrops on linen. 40 x 30 cm.

Javi Cruz. Kobold (La luna), 2022. Silver nitrate fused on iron, magnets, pine wood. 77 cm ø. / Kobold (Las nubes VII), 2022 - 2023. Linseed oil, cobalt and titanium white pigments on linen, pine wood. 30 x 40 cm.

Javi Cruz. Instalación Kobold Nubes, 2023. Linseed oil, cobalt and titanium white pigments on linen, pine wood. Variable measures.

Javi Cruz. Kobold (Las nubes VII), 2022 - 2023. Linseed oil, cobalt and titanium white pigments on linen, pine wood. 30 x 40 cm.

Javi Cruz. Instalación Kobold Nubes, 2023. Linseed oil, cobalt and titanium white pigments on linen, pine wood. Variable measures.

Javi Cruz. Instalación Kobold Nubes, 2023. Linseed oil, cobalt and titanium white pigments on linen, pine wood. Variable measures.

Javi Cruz. Kobold (Las nubes V), 2022 - 2023. Linseed oil, cobalt and titanium white pigments on linen, pine wood. 30 x 40 cm.

Javi Cruz. Instalación Kobold Nubes, 2023. Linseed oil, cobalt and titanium white pigments on linen, pine wood. Variable measures.

Javi Cruz. Kobold (La luna), 2022. Silver nitrate fused on iron, magnets, pine wood. 77 cm ø.

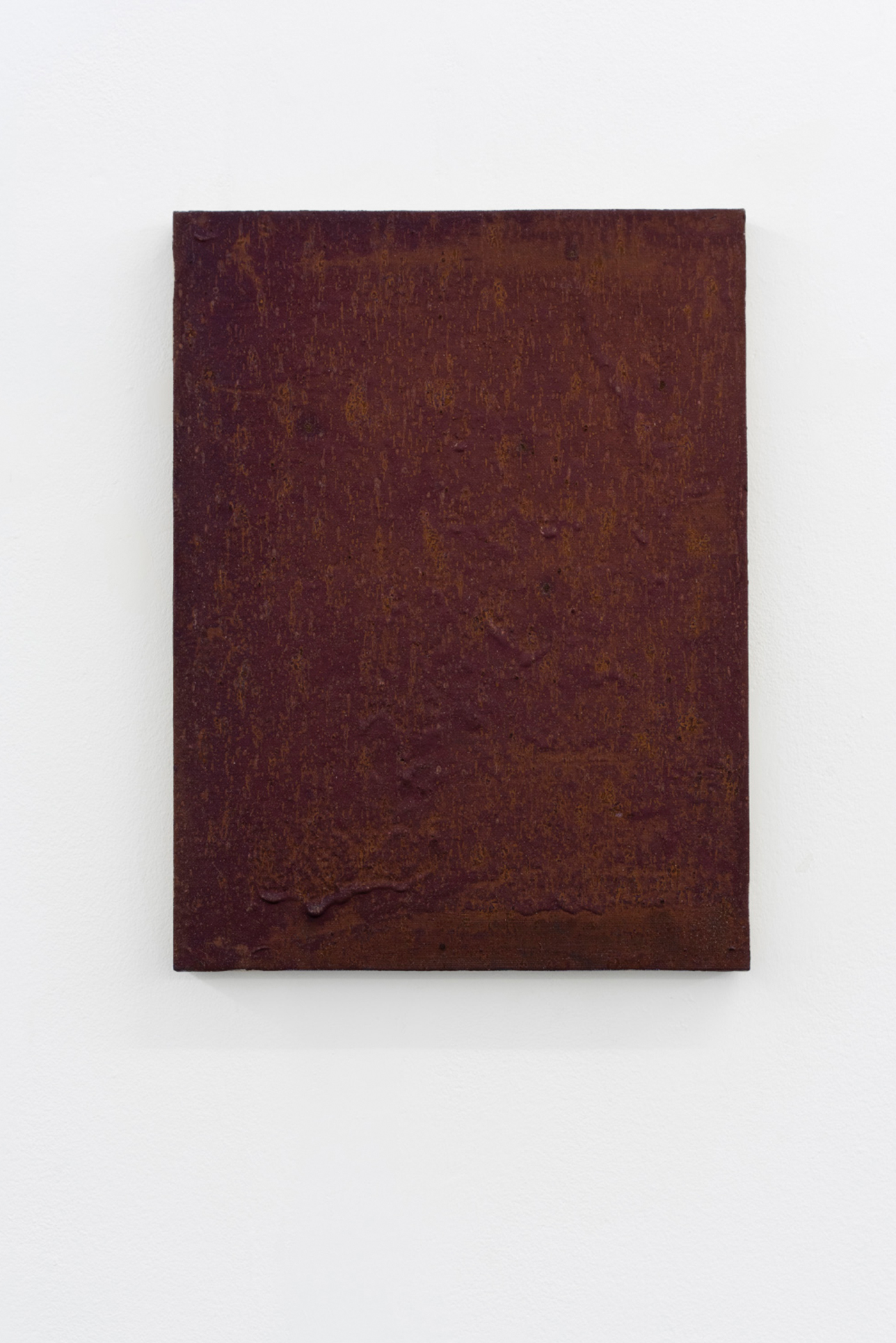

Javi Cruz. Kobold (La luna), 2022. Silver nitrate fused on iron, magnets, pine wood. 77 cm ø.

Javi Cruz. Kobold (La luna), 2022. Silver nitrate fused on iron, magnets, pine wood. 77 cm ø.

[/caption]

Press release

water sky hole

There is a mountain without ground and, in the middle of it, a hollow, a hole. As the mountain grows in solemnity, the hole, on the other hand, gains in discretion. Serene, it never disappears. We could say that it resists or is biding its time; I like to think of it caught up in the pleasure of the plot, oblivious to the epic of the outcome. Here I discover a possible, almost secret way in to a cave inhabited by invisible presences that guard and take shelter from the dangers lurking outside, under the glaring light. Blinding light. I worm my way inside the fragmented story of a life made of many others, of the endless chain of stories, snippets and anecdotes, and also of empty memories that are confused with living fictions; with imagination, desire and with family legacies which are also popular; with the violence of the sacred in the profane and the poetry of the profane in the sacred. Inside, I find the voluptuousness and pleasure of the shared instant, of learning incarnated, encapsulated in the tunnels of the body; with the increasingly more pressing urgency to keep on making, modelling, telling stories, moving and being moved.

Javi Cruz says that “to narrate the world all you have to do is begin with a corner.” In my daydreams this corner is curved, sinuous, in consonance with a time and a world of softer or undefined forms, with “a flowing like a warm wind yet slower,” an overflowing riverbed, a free and more intuitive course, with no set beginning or end, like a little girl totally absorbed in her absolute present. In my mind, I keep sanding down, obstinately trying to soften the rigidity of its edges, the nook where dust often gathers, that dust we are in pain. Corner, hollow, hole, bite, cavity in the body or in rock; from floor to ceiling, from mouth to anus: every form of beginning is essential to expel what seems to burn on the fingertips and can no longer be saved.

In the course of life, some people need to travel thousands of kilometres, to stay overnight in a different city every day, and there are those who need to be able to touch the walls of their bedroom with their hands and eyes. To savour each new crack, to swallow the most insignificant morsel, be disturbed by the shadows and ghosts. A room at home; a home in a neighbourhood; and in it, the graveyard; inside it, the mountain; from the outskirts to the centre; on other outskirts, another mountain, more mount than mountain; sometimes to the village, “the invisible village of the oldest memory,” and sometimes to the sea. The sea and its longing like piped music; its smell, the cobalt colour that impregnates the eye and its reflection of the sky, the one that inundates Kobold like “in the hydrangea a blue explodes in the air that comes from iron and turns/ the confines into beauty, the hydrangea.” The sun splatters the cloud gathered up in the dusk, taking care that little flies and seeds exploded in the damp breeze do not stick to the oil in a desperate effort to cling onto the material transcendence—here obsessive and abundant—that enables death. The cloud gives way to the moon; oil to fire.

You can look up at the sky or you can imagine it hidden behind the untainted coffering of a baroque dome almost perfect in its material restraint: lie down on the cold marble, look up to catch every detail and lose yourself in that horizon drawn by prostrate, diminished bodies. In San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane some students lie engrossed on the church floor under Borromini’s dome, following the precise instructions of their art history classes. There is nobody else there, apparently; just them and the enthusiastic faith of their youth. “One enters sky-caves squatting down, crawling, becoming smaller. Only if you know how to become microscopic will you find refuge or be able to move about in them.” Roger Caillois called the nothingness of the sky emptiness and that of the mountains cave. Both nothingnesses seem to come together in Kobold, where it is also possible to see from above and, on the contrary, to intuit the ground through the thickened dryness of the plaster and the esparto: the discreet yet persistent shimmer of the blurred boundary between the plaster and the straw. “We followed yang; we found yin. I am grateful. My heritage is the wild oats the Spanish sowed on the hills of California, the cheatgrass the ranchers left in the counties of Harney and Malheur. Those are the crops my people planted, and I have reaped. There is my straw-spun gold.”

Everything is inside, everything gives shape. Sharing certain legacies weaves invisible threads, beyond time and space, in an ongoing exercise of self-revision and recognition in and with others. Magic enables us to talk without the need for words, perhaps because those already shared are innumerable: thoughts spoken out loud, some unsteady, that sustain us and give us breath. I wonder whether the intoxicated breath of those men poisoned by their own discovery would also be blue, the colour of hydrangea, when they cry out, halfway between superstitious and desperate, “Kobold, Kobold!”; still poisoned today in cobalt mines. It seems that some things have not changed that much, not even the gesture, the quasi-blind insight of someone, almost always old, almost always humble, who looks and senses the drop before it rains. When it does arrive, I propose, like others before us, to sink into the earth and let the earth close around us, now that this water from the sky does make a hole.

_Beatriz Alonso

* Quotes and citations from Roger Caillois, Javi Cruz, Ursula K. Le Guin, Luz Pichel and Alejandra Pizarnik