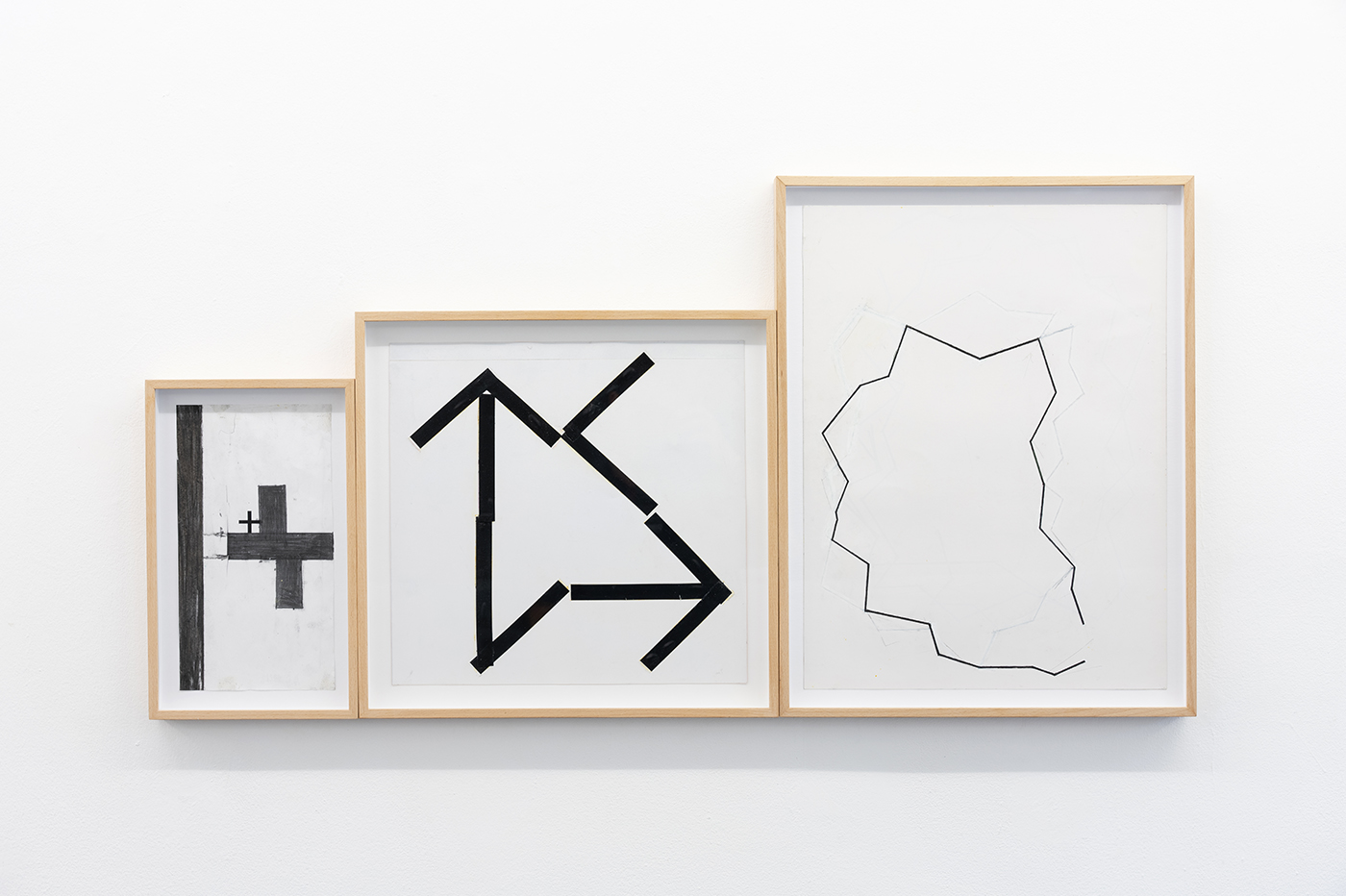

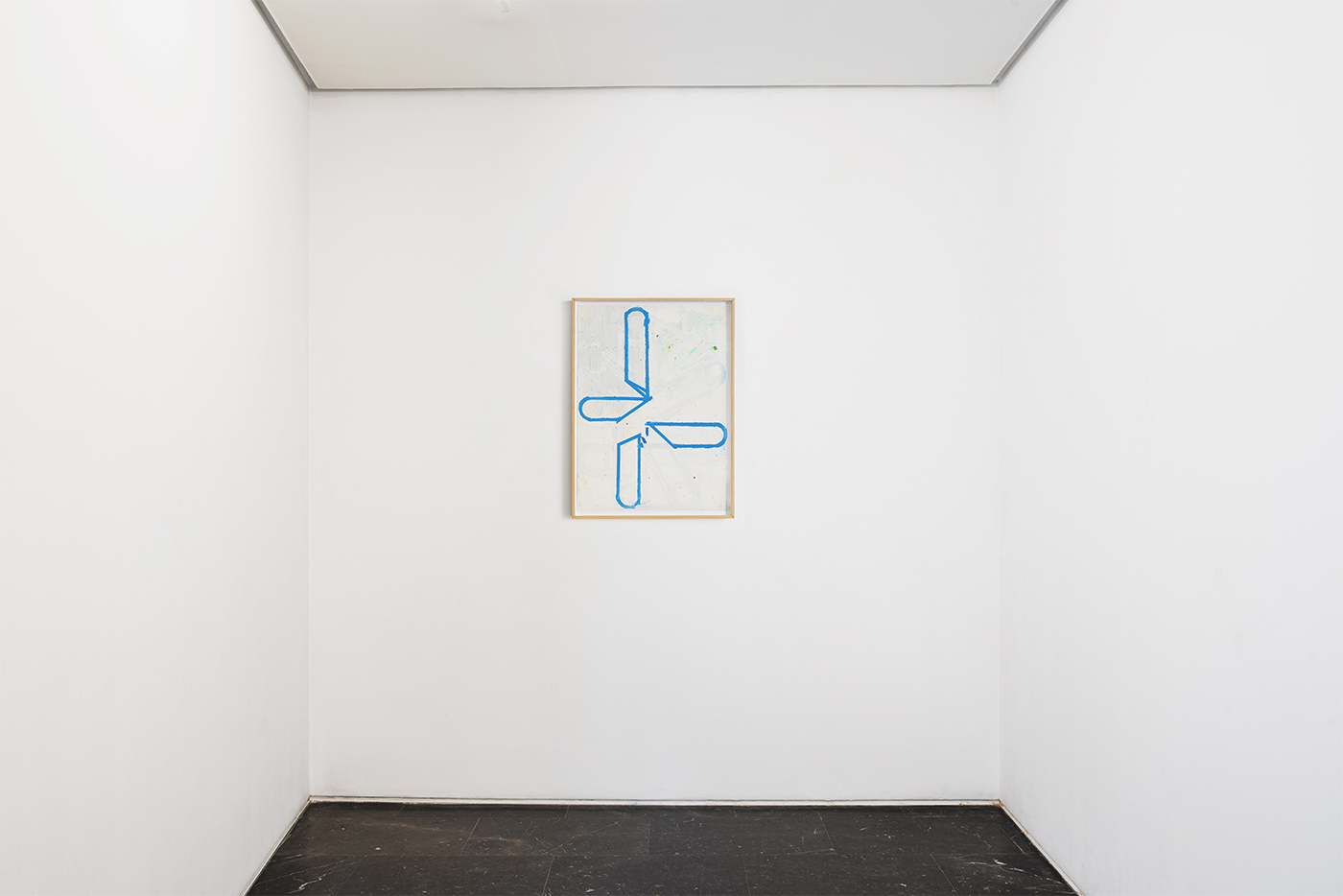

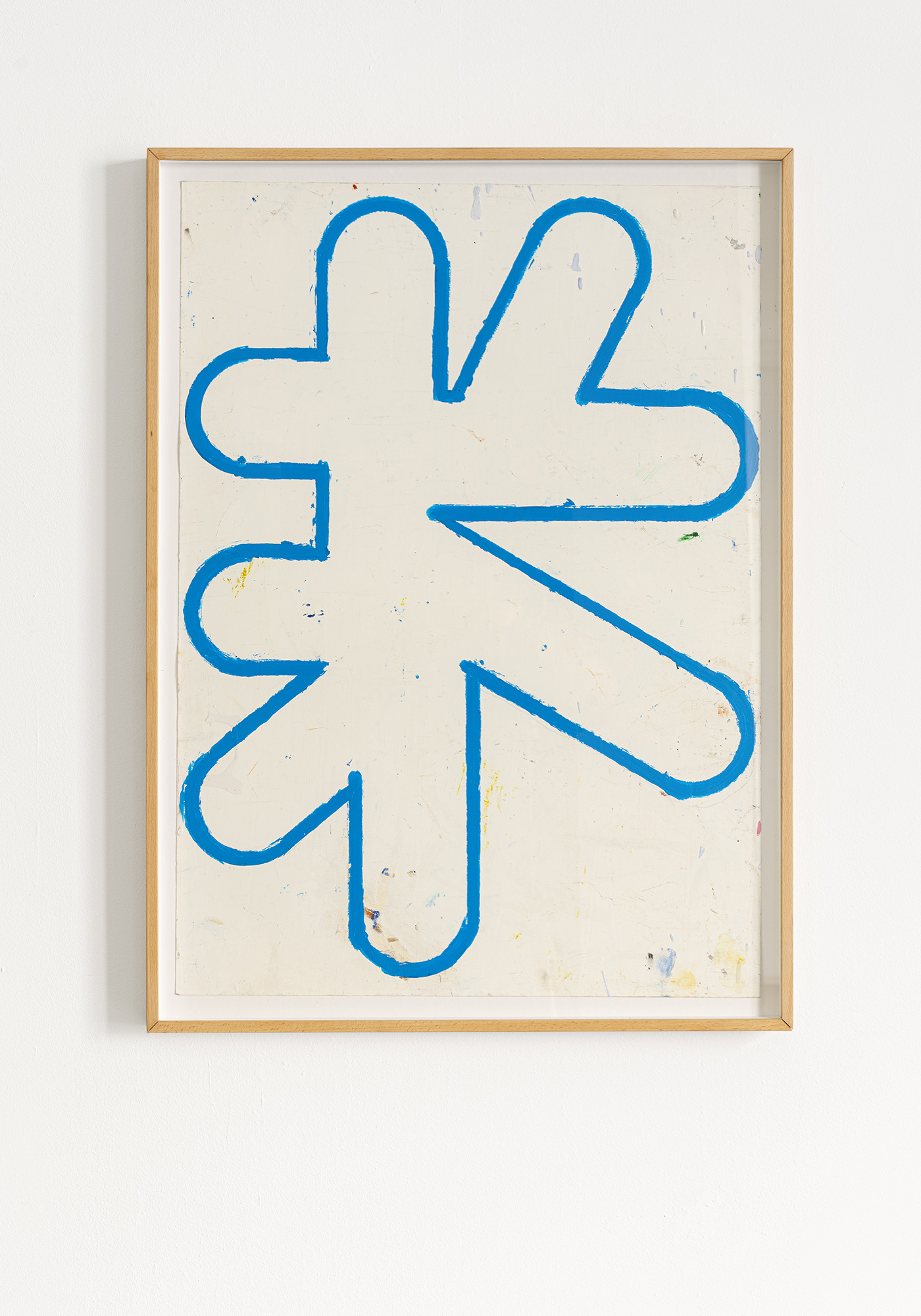

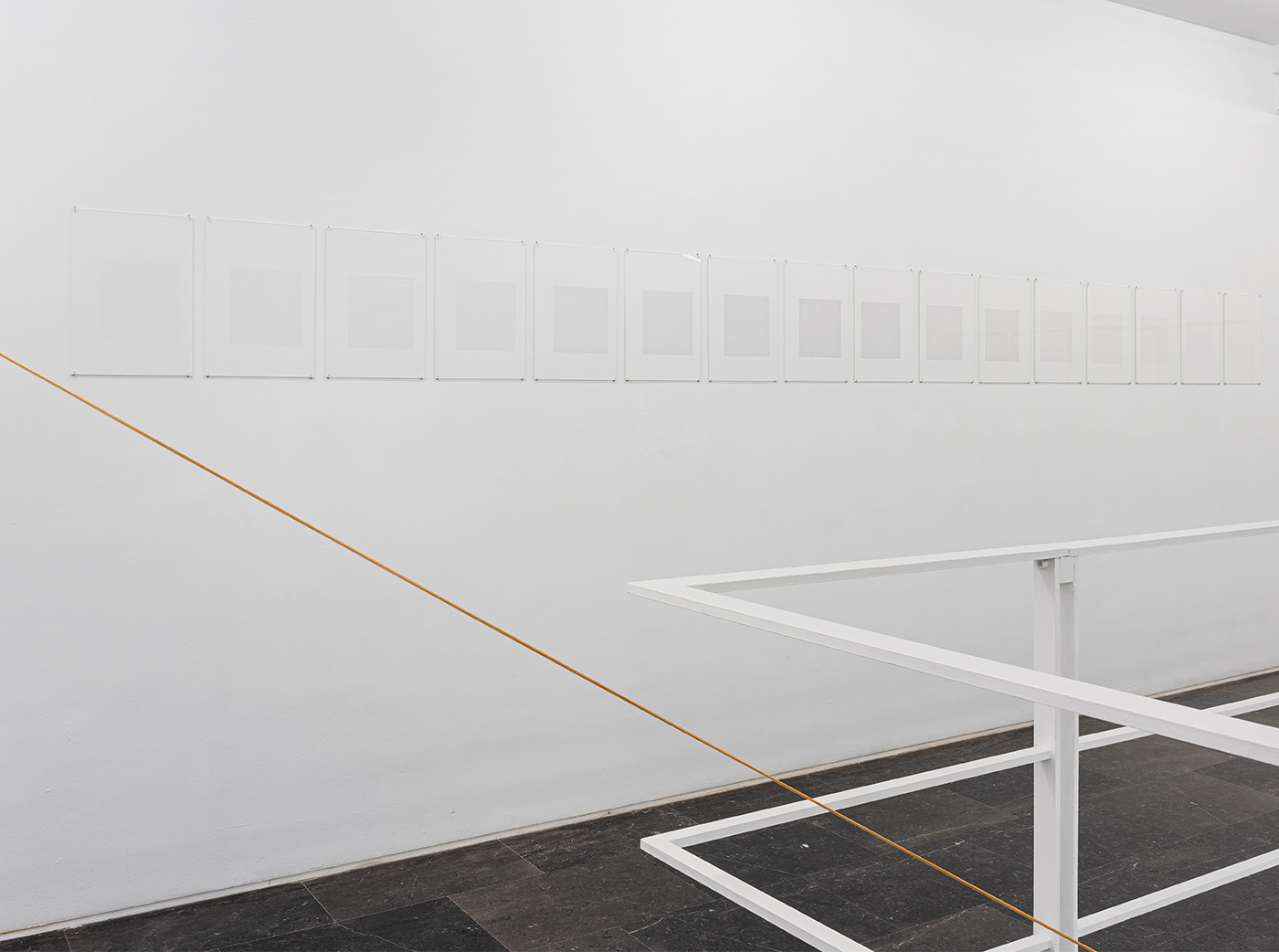

In this exhibition, Trompe l’esprit. Algunos tipos de espacios (Trompe l’esprit. Some Kinds of Space), the artist Rubén Guerrero (Utrera, Seville, 1976) examines the spatial logics circumscribing contemporary experience, its historical foundations and its cultural repercussions. The paintings hanging on the walls of Galería Luis Adelantado bring into play a whole barrage of quasi-flat artefacts that operate as places to register and accumulate information. In Trompe l’esprit Guerrero continues to pursue a personal taxonomy of singular spaces in late-capitalism. After contention mechanisms such as enclosures, gates, fences, screens, and frames explored in prior iterations, he now turns his attention to constructions designed for circulation, whether it be of information, of bodies or of material. In the gallery space, visitors will come across recognizable architectures that at once welcome and reject them. Constructions akin to staircases suddenly transform into tangential shelves. The railing of a pulpit becomes steel bar fencing. A burrow fortifies into a stockade. Multi-directional signage transmutes into a hyperbolic railing that prevents us from passing a level crossing in our progress towards the horizon.

These spaces delimit any expansion of the visual field of the spectators, who Guerrero punishes like children against a wall, foreclosing their access to the world promised by “the painting as window”. His works eschew any representation of the nooks and crannies of his privacy, of his experiences or psychology —something which would push the time of the painting to somewhere long prior to its observation. In fact, Guerrero wishes to activate the time of painting during the spectator’s encounter with the canvases, like the timer of a bomb about to go off. He wants spectators to construct from scratch the scenario placed in front of them, putting their memory, desire, or imagination to work without having to fall back on associations that situate them outside the canvas. What matters is not what these scenarios might have been but what they will be. For this reason, Guerrero employs ambivalent motifs that shun conclusive readings, creating a kind of infrastructure that permits the circulation of information; a support in which each individual can create their own discourse. Emptied of all spatiality, reduced to situations that the painterly materials produce on the canvas, Guerrero’s images offer us an aesthetic experience without an escape valve. Disguised as disciplinary self-indulgence, the gesture camouflages its goal of yanking art from the prescriptive networks of language and subjectivity woven by the capitalist overuse of the image.

In his response to the contemporary mass circulation of images and the inherent devaluation of their meaning, Guerrero’s painting leverages some of the axioms broached by modern art history. His practice veers between Daniel Buren’s generic stripes and Jasper Johns’ muted targets. As the US critic Leo Steinberg contended, the rise of the mass media during the post-war period brought about a radical shift in the spatial conception of painting. Up until then, the painterly space—grounded in Renaissance perspective—had been conditioned by the upright posture of the spectator, acting as a prolongation of the visual field in a process analogue to the perceptive exploration of surrounding nature. However, the mass mechanical reproduction of images and their circulation called for a conceptual reorientation of the artwork-spectator relationship. Now it was time to work with a new kind of space, antithetical to the openness of the visual field and closer to the materiality of the canvas itself: a conceptually “horizontal” plane proper to modern capitalist culture, like the studio floor, the work table or the display case for special dinnerware. It could be, as Steinberg argued, “any receptor surface on which objects are scattered, on which data is entered, on which information may be received, printed, impressed—whether coherently or in confusion”. 1

In iterations prior to Trompe l’esprit, Guerrero questioned the material aspects of images on the canvas. He focused on resolving the quantity of pigments they required to be identifiable, the function of the limits between their respective surfaces, the alterations of the brushwork necessary to conjure their textures, or the role of chromatic contrasts in arising the sense of depth. As a result of this process, the images seemed like surfaces which were stained, folded, punctured, wrinkled, ripped and even as limp as kitchen towels suspended from hooks. In short, they took on heft and occupied a space, making their materiality explicit. Now, Guerrero radicalizes those precepts in order to centre on the material and spatial parameters that enable the contemporary visual experience. Following Steinberg’s logic, we could say that, here, more than on the images, Guerrero focuses on the materiality and the spatiality of the floor, the display case or the table that contains them. 2

In Guerrero’s canvases the visitor’s body confronts spaces that are neither scaled up nor down. With a height of roughly three metres (a dimension that has conventionally modulated and regulated the architectural interiors that house the Western body), the paintings the artist is presenting at Galería Luis Adelantado dispense with the redimensioning operations proper to representation, in which spaces external to the canvas are nested within the confines of its stretcher or are abstractly schematized. In Guerrero’s paintings, the architecture of the canvas at a scale of 1:1 does not represent a space: it constructs it. The visitor is projected in his painterly spaces, which are as dense as sarcophagi: this becomes the body about to climb up on the rostrum in Untitled (First and Second); projecting their voice from the pulpit in Untitled (Parapet); succumbing to the hypnotic gravitational centre of Untitled (Zero Point); trying to climb the tangential stairs in Untitled (In Eight Steps); hibernating in the impossible mesh of sticks, at once welcoming and rejecting, in Untitled (Burrow).

This coincidence between the logics contained within the canvas and that of the spaces beyond them dynamites any distinction in formal matters such as changes of plane, centrality, transitions or the delimitation of the visual field, which operate under the same parameters inside and outside the painting. The same happens with material matters. In other words, in Guerrero there is no difference between the flaking, erosion, scrawls, tarnishing or repainting that takes place on the canvas and the physical-chemical processes that the material undergoes off it. Or do we not perhaps notice the decrepitude of a podium through the peeling paint on its surface, as happens with Untitled (First and Second)? Do we not spot the gradual corrosion due to the appearance of reddish stains on a uniformly lacquered surface? What is the difference between a pentimento and the marks of painting to previous distributions on the wall where the stairs of Untitled (In Eight Steps) are now fixed? Does the centre marked by the arms of Untitled (Zero Point) not coincide with the true centre of the canvas?

By taking spectators out of their private world, by confronting them with the silent spaces of information accumulation that surrounds them, by forcing them to recompose data in a coherent discourse, Guerrero’s painting exacerbates the logics of landscape that govern late-capitalism. In short, in Trompe l’esprit, the artist exposes us to those spaces that seek to contain our experiences as mere data while at once disavowing our presence as subjects.

_Lluís Alexandre Casanovas Blanco.